On a recent afternoon at Austin Public Health, a fax machine spewed out 289 reports of COVID-19 test results from local labs, some of which had been run 10-12 days earlier. Dedicated staff then went about the laborious task of manually entering those results into a database, results of limited utility due to their tardiness.

This scene is emblematic of the sorely inadequate infrastructure plaguing our nation’s public health system. The lack of an integrated and computerized system to report “notifiable” infectious diseases in Texas is just one example of this inadequate infrastructure.

Years of inattention, characterized by underinvestment, funding cuts, and lack of political will and leadership, has resulted in a public health system completely unprepared to handle the crisis we now face.

Our system is fragmented in terms of both organizational structure and funding. This originates at the state and federal levels but has its greatest impact on local health authorities, where too few staff members work within an archaic system while struggling to keep up with the exponential growth of a viral pandemic. There are, for example, only half as many epidemiologists as required for a jurisdiction our size.

Because of inadequate funding, infrastructure, and staffing, our public health departments are forced to act in a reactionary, damage-control mode rather than proactively applying the science of epidemiology. Consequently, in a time of crisis, it is impossible to quickly expand resources to appropriately adjust and respond.

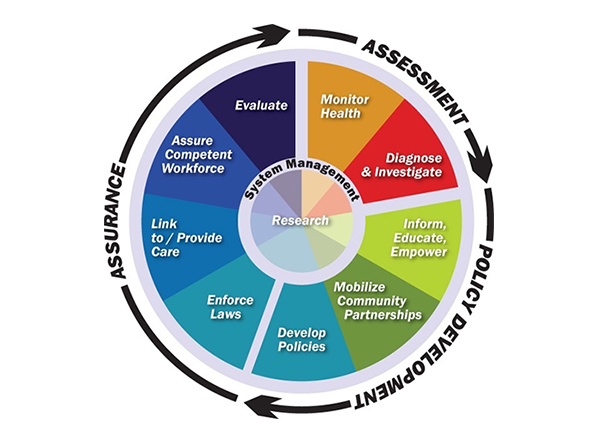

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website has a section that explains the structure of our public health system and describes “The 10 Essential Public Health Services.” It is encapsulated in this colorful graphic:

A PowerPoint accompanies this graphic, describing in more detail the activities that should occur under each of these services. A robust, well-funded public health system such as this could make great progress in dealing with the challenges of chronic disease, substance abuse, and mental illness in normal times, and pivot to confront an infectious disease crisis when needed. After a quick review of this 10-point model, however, it does not take long to realize that the promise of the model is far from realized.

With innumerable budget constraints and competing priorities, it is easy to understand how efforts focused on disease prevention and chronic health problems get shifted to the back burner. It seems expensive to invest in public health infrastructure. But like an insurance premium we pay to protect ourselves in times of unanticipated calamity, the cost of adequate public health infrastructure seems modest compared to the estimated $7.9 trillion (according to the Congressional Budget Office) this pandemic will now cost us.

The old adage has never been truer. An ounce of prevention could have been worth a pound of cure. Make that a whole ton of cure.